Thinking on a Friend

by Scott Thomas Anderson

‘A Life’s Work Still Illuminates the Past’ in

Sierra Lodestar

The once-abandoned town of Les Baux-de-Provence

“We are but dust and shadow” – Horace

Eleven months after John Johannsen passed away, the studio he’d spent half a lifetime working in was claimed by a fire in the night. It was the worst art disaster in the history of the California Gold Country. Not only did the building house most of Johannsen’s unsold paintings, but the space itself – its wild and musing dimensions – marked the region’s highest achievement in functional art. In my first story ever published, I described it as an “artificial grotto hyper-illuminated by a strange menagerie of painted life.”

Johannsen’s piecesmade a splash in San Francisco in the 1950s, but the unfettered brightness of his brush truly developed when he was living in France.

A year after the inferno, the last bits of ash and soot were cleared from the remnants of Johannsen’s world; and I was traveling though the French region of Provence, thinking a lot about my departed friend.

The buildings of Les Baux-de-Provence

The buildings of Les Baux-de-Provence

are carved from granite

Provence is the birthplace of impressionism. It remains a cascading tapestry of wheat, vines and olive orchards nearly frozen in the 19th century. I was visiting Les Baux, a tiny, medieval town perched on a cliff overlooking the valley of Saint-Remy-de-Provence. Johannsen spent time working and painting there in the 1970s. Saint-Remy is best known as the village where Vincent van Gogh was institutionalized after his collapse in 1889. The stone houses and rocked lanes of Les Baux lift along Saint-Remy’s southern horizon, rising as a jagged, bay-gray hamlet literally carved out of the granite mountain.

During the era Van Gogh was recovering, Les Baux was an abandoned relic of the Renaissance, a place whose only life was a howling breeze that moved through its leaden fortress and empty terraces, mustering strangely hypnotic noises called “the minstrel wind.”Van Gogh would sit outside the asylum and paint Saint-Remy’s landscapes as this gale whispered over grapes and tree-dusted ridges, moving up the mountain where its voice moaned inside the cold, empty dwellings of Les Baux. One can only imagine how such haunting elements of nature channeled into the works Van Gogh painted at the time, like “Irises,” “Wild Roses” and “Starry Night.”

Peering southeast from Les Baux, one catches a view of the hills outside Aix, where Paul Cezanne spent much his life painting glimpses of everyday Provence, such as “The Blue Vase,” “Women Bathing” and “The Card Players.”

Modern Baux-de-Provence is filled

Modern Baux-de-Provence is filled

with wine bars and art galleries

Similar tothe French impressionists, Johannsen’s technique reflected how nature touched his spirit. That’s evident in paintings like “A Trout in the Meadow,” an orange and ruby-red arrow of uninhibited freedom soaring through the dark. It’s a shimmering launch – a projectile of hope. “Broken Fish Plate” shows another side of Johannsen, a fractured fiesta of running thought, a reveling Argonaut swimming through the hard tide of experience. A similar meditation hangs in my house: It’s a plump fish drifting in misty white space, with its cyan belly made of water and wine, its eyeball from a landing sparrow, its sleek back touched in pears, plums, cranberries and songbirds. Sometimes, when my writing is bogged down, I look over and realize that my mind can swim away with that fish, that it can escape into new pods and brighter perceptions.

Johannsen’s glow was evident even in his late paintings like “Blue Jays,” a graceful tangle of azure birds and springtime petals woven into the kindled pattern of a flower bouquet. He created a series of bouquet images, which isn’t surprising: One of his favorite stories about living in France involved the afternoon he’d ordered a large arrangement of flowers and the arriving florist asked for one of his paintings as compensation rather than cash. It was an anecdote Johannsen always said punctuated the French mindset.

The valley of Saint-Remy-de-Provence

The valley of Saint-Remy-de-Provence

I kept such memories in mind as I moved along France’s Mediterranean coastline to Antibes, a small town looped in brick ramparts, caressed by ivory beaches and palm trees glowing against the teal shimmer of the sea. Antibes’ castle-manor is the Chateau Grimaldi, and it was here that Pablo Picasso regained his creative energy in 1946. Staying in the chateau, he made 23 paintings and 44 drawings inspired by Greek and Roman folklore tied to the nearby Liguria. Picasso was so grateful for what Antibes had done for his energies that he handed most of the artwork over to the Chateau Grimaldi, which was then converted into a modern museum. Today it’s called Musee Picasso.

Strolling through Antibes, I soaked in the daily rhythms of life. That same quiet calm that relaxed Picasso can still be felt. The heartbeat of Antibes is its open-air market: It’s a panorama of farmers with fruits and vegetables, butchers wrapping meat under dangling hooves and logs of salami, and smiling dairymen selling all shapes, sizes and assortments of cheese. Its booths run along outdoor cafes and wine bars under maple trees that speckle the buildings’ storm shutters. I’d heard about such scenes many times from Johannsen.

The French town of Antibes

The French town of Antibes

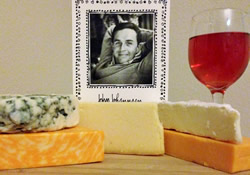

“You’d cook with fresh ingredients each night; you’d have a nice bottle of red wine on the table, and then you’d put out a little dish of something from these fabulous assortments of cheeses,” Johannsen recalled. “It was a good life.”

That commitment to the day – to the moment – is the essence of the art Johannsen made in France; and it runs through all his paintings once shown at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, or the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, or the Hammersmith Gallery in New York. But more than Johannsen’s accomplishments, what I remember about him are the little touches of imagination he encouraged me to embrace: the value of good cheap wine merged with big French cheeses; the range of enlightenment comes with international travel; having concern at the sight of suffering; resigning one’s self to the ways of nature; using sarcasm in the face of absurdity; finding meaning through the strength of friendships.

Johannsen’s paintings may have graced the best galleries in the nation, but his most impressive work of was the way he existed – a crazed confusion of elaborate simplicities daringly soaked in the world’s most timeless colors.

John Johannsen

John Johannsen