Lost in Lorca's Spain

by Scott Thomas Anderson

Granite Bay View

Eventide on the edge of Spain has a veiled light called “duente.” It’s an alchemistic rise of the spirit, an internal mystery swelling under the ribs.

Understanding duente was an obsession for the writer Federico Garcia Lorca: In the years before his nation’s civil war, Lorca defined this feeling as Iberia’s deepest state of rapture — a creative epiphany born from stains of blood and the echoing voice of the outcast. Today, following Lorca’s path through Andalucía offers a vision where duente is everywhere.

Seville

There’s a poetry to watching the sun rise from rooftops in Seville. Champagne light drizzles the maze of palm trees, terraces and stolen mosque domes as antennas laced in weeds shimmer under the sky. Crowning the district is Seville’s cathedral, a desert-colored beauty absorbing the dawn, brightening from beige to sorrel along the blades of its 16th century grandeur.

It was here, during Holy Week of 1921, Lorca began writing verses for “Poem of the Deep Song,” an ode to the roaring emotional intensity of his homeland. Little has changed in Seville’s Old Town since he penned those lines. The Andalusian sun is still blinding by noon, and people still crowd into tapas bars scattered from Barrio Santa Cruz to narrow lanes near Plaza Nueva. These hideaways from the heat embrace a shared experience: Black-eyed, mounted bull heads; crescent hog haunches dangling from hooks; framed portraits of long-dead matadors, picadors and banderilleros. Lamplight glints on ornate mirrors and sweating vases of Sangria stuffed with fruit drifting like severed body parts.

Strangers here taste Seville’s pride through acorn-fed, Iberian jamone, which is Spanish for succulently wet, paper-thin slices of cured ham. Jamone is the city’s culinary identity, one that’s only elevated with a crimson stream of Rojhan Grand Resevra splashing into a glass over shrimp drowned in garlic, green chilies and olive oil. Locals use this array of flavors and fermentation for bracing against the midday sun.

Lorca once described Seville as “a city lying in ambush for long rhythms.” He sensed that in the evening’s long rose kindle, as well as the stabbing notes of its ageless folk music. It’s an aspect of Seville well embodied in Flamenco dancers like Maria Jose Leon. Accompanied by guitarist Manuel Torres — and a ruffled, weathered singer named Pepe “El Ecijano” — Leon prepares for her journey by idling on the stage, her shoulders wrapped in ebony mantle, her strong hips holding a statuesque stillness. Torres and El Ecijano start snapping fingers, clapping hands and stomping their shoes on the floor. It’s a careless cadence, a peasant percussion that invites the guitar’s growling arpeggios to unlock this barrio’s secrets. A hurting defiance overtakes Leon’s expression, though she doesn’t move. The audience hears only a mania of nylon guitar strings and El Ecijano’s voice wavering from anger to agony. Then Leon turns and twirls, a sweeping thrust in her back, her arm slashing up to the sky. The dancer’s feet crack the wood with an aggressive grace. Sweat is beading down her neckline, but she only moves faster as the music builds momentum, she only reveals more confessions through the sorrow climaxing in her face.

“Her long silk train sways back and forth,” Lorca wrote of a dancer he knew. “She calls Death, but Death never comes.”

Photo by Scott Thomas Anderson

Hiding in the Hill Towns

East of Seville, the roads lead to whitewashed fragments of rural life essential to knowing Lorca’s world. These are Spain’s lost dens of the past, bundles of bone-colored houses and palaces that cling to shattered bluffs overlooking the southern plain. It’s known as the Ruta de los Pueblos Blancos. Of its hamlets, Arcos de la Frontera reaches highest into the clouds.

Dual churches are perched on Arcos’ cliffs, each with a salmon, sun-blasted bell tower that plays on the town’s trance at sunset — that lulling mirage of stone mingling with the pink of twilight and approaching stars. The church bells ring even while wine glasses are still filling in the plaza, even as steaming fish and diced octopus are still landing on tables pooled in olive oil. A cloistered nun’s hand passes cookies through a tiny window in the door of her convent. And when night envelops Arcos, those sitting on its ledges face the Andalusian moon, a lucent bulb peeking between pearl pillows that drift through the darkness. Lorca had contemplated the land above this nocturnal abyss: “The oil lamps are all put out,” he wrote. “Some blind girls question the moon.”

Daybreak sparkles on the Guadalete River below as it turns through olive orchards near the open road to Ronda.

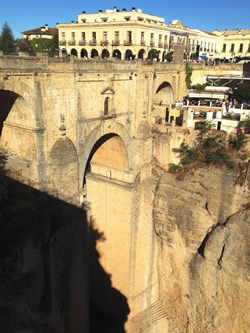

Unlike Arcos, the town of Ronda rides a deadly gorge, its quarters split on knife-flat ground flanking the precipice. Ronda boasts the oldest bullring in Spain, a sight that’s mesmerized Americans as much as the pale houses spackled to its canyon-falls. Photos of Ernest Hemingway drinking with town elders hang on aging walls. A bust of Orson Wells glances out at windy trails and sun-lit vineyards. Hemingway spent his last birthday in Ronda. Wells had his ashes scattered in one of its gardens. The shade of human endings is ever-present on these jagged cliffs. One matador felled by a bull demanded his body be buried on the spot, somewhere under ring’s hard, red dust.

Lorca was no stranger to bullfights. For him, the blood, desperation and dueling was more than a spectacle of bravery, it was a ritual memento of death — a shadow that fell long on his poetry. Lorca’s best known work is an elegy to the bullfighter Ignacio Sanchez Mejias, his friend who was gored to death in the ring in 1934. The poem’s images and rhythms can cut into a reader’s skull: “Now the bull was bellowing through his forehead, at five in the afternoon, the room was iridescent with agony, at five in the afternoon.”

Ronda’s location on the empty backroads also makes it a symbol for darker freedoms once pervading the land. Throughout the 19th century, the town was a mustering point for “bandoleros” the lawless highwaymen who lurked under its cork trees or between its hard, golden hills. The best restaurant in Ronda now stands just beyond the gate that stopped these despenaperros: Casa Maria is a sparse family kitchen that serves homemade wine, blissful pan-can tomate and mind-blowing seared tuna. A moonlit stroll from its doors goes by the house filled with antique weapons left by the bandoleros, those razor-edged symbols that haunted Lorca’s dreams of Andalucía.

“The dagger enters into the heart,” he jotted in one verse, “like a ploughshare into the barren waste.”

hitching the town together was built in 1751. Photo by Scott Thomas Anderson

Granada’s Dance of East and West

Granada.The city where Christian martyrdom meets Arab majesty. It’s Madrid’s basement of mirrors. It’s Africa’s balcony of hope. From its labyrinth of cypress trees to its horizon of parched mountains, Granada is a study in beauty built on blood--the continuing re-conquest of the human spirit.

It’s also the heartbeat of Lorca’s verse.

The poet’s hometown survives as a staggered tide of caves, balconies and courtyards viewed from terraces over the Plaza de Bib-Ramba. Here one sees Granada’s lasting riddles, the jutting ribs of an old Moorish town, the lime trees fountaining on gilded windows, the desert-cut roughness of the city’s looming cathedral. Further off, shrubs and fruit trees wrap a palatial fortress of Islam known as the Alhambra. A modern neighborhood sprawls south, but north is the pearly maze of Sacromonte’s gypsy town, lost and strange and drilled into the face of a wind-scrubbed hillside.

All these sights hint at the way Granada’s cultures have baked together through the centuries under a brain-boiling sun. Visitors still feel the heat of their marriage in the Eastern silk market, where lamps, rugs and spices snarl a corridor just beyond the chapel displaying the coffins of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, the very monarchs who drove the Moors from Spain in 1492. Granada’s contradictions don’t end there: The dawn of Jewish scholarship that once flourished in its streets is etched into Barrio Realejo’ stonework, the grim whisper of a people forced into exile in the 10th century. Granada’s algetic past can make for disquieting dreams, yet the city is alive with energy, especially in kitchens where Spanish, Jewish and North African influences have fused in more inspiring ways. The lively tapas bars are famed for plates of breaded sardines or the cool zest of their gazpacho. Dishes of Solomillo a la Pimienta also tell a story through pork loins slathered in a thick, creamy pepper sauce. This is the other side of Granada’s evolution, the place where Spain’s Mediterranean meditations collide with the best aromas.

Granada’s style of flamenco is sprinkled in Arab poems and Hebrew laments, but its true signature involves the way gypsies pulled those memories into their own roiling passion. The city still breathes this musical tradition in the alabaster tunnel-taverns of Sacromonte. Here men flourish guitar chords from rickety wood stools. Singers pitch their mournful cries down a curvature of hard, white earth. Women spin their dresses and keep castanets popping with the gentle motions of their hands. Lorca enjoyed countless hours in Sacromonte’s caves as a teenager. He knew that the Spanish Roma had shaped an exquisite pain into the land’s songs, as much as Catholic liturgical chants and Moorish calls in the wind.

“Bulrush and twilight tremble at the edge of the river,” he reflected in Gypsy Siguiriya. “The grey air ripples. The olive trees are charged with cries.”

Lorca was on a visit home to Granada when the Spanish Civil War erupted in 1936. The city quickly fell to fascist militias. When these oppressors discovered that Lorca — an outspoken defender of democracy, women’s rights and intellectual freedom — was back in his city, their secret police made him a thread in Granada’s grand tapestry of tragedy. They took Lorca away after sundown. Some remember him being marched into the old cemetery behind the Alhambra. Others claim he was lead to an olive orchard near a spring the Arabs called the Fountain of Tears. What is known is that Lorca’s beloved Andalusian moon couldn’t bear to watch that night as the firing squad took position. One hopes, through poetry, Lorca’s spirit was already flying.

“Down a road travels Death, crowned with withered orange blossoms,” he’d jotted. “Death sings, and sings a song with her ancient white guitar, and sings and sings and sings.”

Photo by Scott Thomas Anderson